| DMH Spotlight - Photo Title | Back |

Dr. Amy Forss

“Capturing Change at the First National Women’s Conference, Houston, Texas, 1977”

AHA 127th Conference, New Orleans, Louisiana

January 5, 2013

To contact Dr. Amy Forss, History Program Chair, Metropolitan Community College, email: aforss@mccneb.edu

Library bookshelves offer several excellent monographs written about the modern National Women’s Movement. Texts, such as Ruth Rosen’s The World Split Open, Barbara Love’s Feminists Who Changed America, 1963-1975, Linda Gordon and Rosalyn Baxandall’s Dear Sisters, and Christine Stansell’s The Feminist Promise provide a more than adequate explanation of a complicated crusade. However, these social and political examinations of the quest for women’s rights offer a chronological straight-forward predominantly text heavy presentation of gender liberation. This afternoon I would like to present a new Second Wave narrative with an alternative focus from a chapter of my current project, Portraits of Protest: The Women’s Movement Media Wars, 1963-1982. Each chapter in my monograph will examine the antagonists and proponents of the women’s campaign through the scope of the media. I am arguing that leading feminists Bella Abzug, Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan and conservative champion Phyllis Schlafly, successfully persuaded American women and men to join their factions by using the media power of books, magazines, newspapers, newsletters, radio, photography and television. Portraits of Protest’s chapter six, entitled “The Spirit of Houston,” explores the medium of photography at the 1977 National Women’s Conference in Houston, Texas. All of the images in the chapter and the ones you will see this afternoon are the work of Diana Mara Henry, the official photographer at this historic one-of-a-kind event. You will be viewing a tiny portion of Henry’s images from her 60,000 photograph collection. Her Harvard degree in Government, Ferguson History Prize and Harvard Crimson photo editor background influenced her images. Henry’s photographs act as stand-alone artifacts rather than contextual augmentation. And, even more important and the connecting relevance to this presentation, they served as visual documentation in The Spirit of Houston, the official published report presented to President Jimmy Carter, the Congress and the People of the United States.

Copyright © 1977 Diana Mara Henry / www.dianamarahenry.com

The 300-page report assessed the status of women, measured their progress since 1848 Seneca Falls and identified current barriers to female equality in America. Basically, the report answered the all-consuming women’s rights question, “What Do American Women Want?” Recently, Henry reformulated the function of her photographs when she quietly but adamantly stated, “I wrote history too.”

The chanting was almost deafening. Arizona delegate Judy McCarthey climbed on top of her metal folding chair and stomped her feet, caught up in the conga line excitement emanating within the Sam Houston Coliseum. She literally swayed under the extra weight of nine months of pregnancy. McCarthey recalled how she precariously balanced to keep from toppling over. Perhaps her unborn child sensed her mother’s elation as she delivered a mighty kick which left McCarthey gasping and grasping the backside of the chair. Her unborn baby had just chosen her name: Equal Rights Amendment, E.R.A. for short. Most of the 2,000 assembled fifty states and six territories elected delegates, 46 commissioners, 400 government appointees and approximately 17,000 observers attending the First National Women’s Conference (FNWC) were celebrating their consent on Plank 11. It consisted of seven words: The Equal Rights Amendment should be ratified. It was the shortest plank and the only resolution of the 26 being voted on during the Houston conference that the wording remained unchanged. Four months later, E.R.A. and McCarthey, now part of the women’s National Plan of Action continuing committee, participated in the White House official report presentation. The small crowd of previous Houston attendees congregated in the Blue Room. E.R.A. somehow landed on President Carter’s lap, but he hastily handed her to McCarthey saying, “Momma, I think she needs you.” After McCarthey changed E.R.A.’s diaper, Gloria Steinem picked up the baby. Nearby, Henry focused her camera and recorded the encounter. The Madonna/Child composition of the photograph demonstrated better than any words the sincerity of the women’s movement being about all women. E.R.A. became the feminists’ poster child

.

Copyright © 1977 Diana Mara Henry / www.dianamarahenry.com

The National Women’s Conference in Houston, Texas began with a chaotic situation on November 18, 1977. Delegates, appointees and observers arriving at the Hyatt Regency Hotel on 1200 Louisiana Street were greeted with an unusual dilemma.

Copyright © 1977 Diana Mara Henry / www.dianamarahenry.com

According to observer Mary Williamson and repeated by other women interviewed for this project, an oilmen’s convention was scheduled to end on November 16th, but when the men understood a government sponsored women’s conference was expected, they refused to check out of their rooms. Their deliberate action caused a hotel lobby bottleneck. Henry arriving at the hotel stopped to assess the lines of people and suitcases. She rode the elevator up a few flights and shot a dozen images from different angles. Her photographs, which appeared in the conference’s official report, spoke volumes about the average man’s response to a feminist conference. Indeed, syndicated columnist Patrick Buchanan called the Texas meeting the “Houston Hoedown.” The lobby crisis eventually righted itself as those who were assigned rooms shared with fellow attendees. It was an auspicious beginning that dispelled the conservative stereotype of feminists being unable to work together.

The hotel lobby confusion faded with the following day’s opening activity, the completion of the torch relay. The relay was the creation of commissioner and Redbook magazine editor, Sey Shassler. On November 19th, the final three torchbearers jogged towards the Sam Houston Coliseum. Carrying the torch high, the trio ended the 2,600 mile relay from Seneca Falls, New York to Houston, Texas. Henry’s iconic image showed Susan B. Anthony’s great-niece and same namesake (third from the left) arm-in-arm with tennis great Billie Jean King, Presiding Officer Congresswoman Bella Abzug, the three torch bearers and Betty Friedan, author of The Feminine Mystique. It was a patriotic image, almost a flashback to the nineteenth and twentieth century suffragettes demanding the right to vote during the original women’s movement. In order to frame this watershed moment, Henry had to run backwards in front of the women while adjusting her shutter speed and recording almost a dozen photographs.

Copyright © 1977 Diana Mara Henry / www.dianamarahenry.com

The multiracial trio of torch bearers Sylvia Ortiz, Peggy Kokernot and Michelle Cearcy, were carefully selected by the conference committee. Ortiz, a petite Hispanic senior at the University of Houston was in her last semester of student teaching. She was excited to be a torch bearer, but she remembers being more scared than excited. She was worried the media coverage would affect her getting a job; the women’s movement was not a popular topic in traditional teaching circles. Kokernot, a 25-year-old marathon runner and unemployed college graduate, hoped she could encourage the Olympics’ committee to allow women competitors in the marathon event. A month earlier, she had run a 16 mile stretch of the torch relay through Alabama. The previously scheduled misinformed runners refused to run; they thought the torch relay promoted gay rights. Cearcy, the youngest of the three, was an African American sixteen year old sophomore at Phyllis Wheatley High School. Recently chosen as her school’s best athlete, she was concerned the photograph session would make her late a volleyball tournament. After all, the three women, who had not met prior to the torch relay, were a golden media opportunity. But when Henry turned her camera on former First Ladies Lady Bird Johnson and Betty Ford, incumbent First Lady Rosalynn Carter and Bella Abzug accepting the torch from the trio, the presence of the First Ladies visually validated the legitimacy of the First National Women’s Conference.

Copyright © 1977 Diana Mara Henry / www.dianamarahenry.com

Three days of plenary sessions followed the opening ceremony. Delegates and appointees followed parliamentary authority guidelines; spoke using Robert’s Rules of Order and adhered to strictly enforced methods of voting. The conference, with its state banners and assigned sitting, was deliberately designed to look and sound like a political party convention. A program for observers included daily seminars on topics such as “How to Run for Office, Marriage, Separation & Divorce, Women in the Skilled Trades and The Media.”

Copyright © 1977 Diana Mara Henry / www.dianamarahenry.com

There was a great deal of political discussions and decisions between the women and few men attending the conference. Their goal was to vote on the 26 planks suggested by the International Women’s Year meeting held in 1975. The resolutions they were considering of course included ERA, but there were also planks on Child Care, Minority Women, Reproductive Freedom, and what Betty Friedan had earlier coined “The Lavender Menace,” better known as Sexual Preference. However, at the conference, Friedan dramatically changed her stance on gay rights to heal the schism between pro-women’s rights supporters. The conviction of this woman holding up a sign, not speaking but airing her anti-gay stance against the proposed lavender plank, was commensurate with her right-wing sisters. The yellow Majority ribbon wearers faction were in the minority (about 400 to 19,600) at the conference, but to them the word Majority represented the majority of American women the conservatives contended agreed with their “Pro-Family” agenda.

Copyright © 1977 Diana Mara Henry / www.dianamarahenry.com

Phyllis Schlafly, leader of the Majority conservatives, Sweetheart of the Silent Majority and author of numerous books including Feminist Fantasies, embraced the Houston meeting as one more chance for media attention spotlighting what she and the “anti’s” considered the “pro’s” misguided agenda of ERA, sexual preference rights and government funded abortions. Schlafly lacked the feminists’ 5 million dollars’ worth of federal money provided by Legislative Bill 94-167, but her media savvy made her a worthy opponent. Schlafly, who Friedan labeled as the “chief agent of the right-wing hate movement against women” proceeded to wage a media war in Houston with the help of her Eagle Forum followers. Texas native Eagle La Neil Spivy knew “the news was always looking for someone to disagree,” and being the wife of a four-star general, she hastily strategized and raised the funds to rent Astro Hall convention center. It was a mere seven miles from the feminists’ conference. The Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, Amsterdam News, and other newspaper journalists appreciated the closeness of the two opposing camps. On Saturday, the 19th of November, Schlafly and 32 busloads of Eagles held a successful one-day rally. The STOP ERA women and men filled the 18,000 seat Astro Hall to full capacity with a 2,000 overflow crowd outside of it as well.

Copyright © 1977 Diana Mara Henry / www.dianamarahenry.com

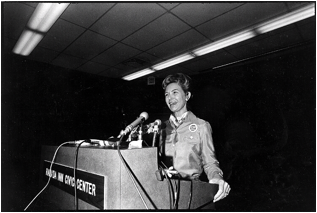

The tireless Schlafly gave a press conference at the Ramada Inn Civic Center that evening and the following morning on Sunday, November 20th, she debated several feminists, including Eleanor Smeal, president of the National Organization of Women and Liz Carpenter, press secretary to Lady Bird Johnson on the political television program Meet the Press. The exposure for both the anti and pro women’s rights factions was invaluable to supporting their movements.

The media coverage of the government funded Houston conference and the grassroots funded one-day opposing rally squarely placed the question of women’s rights on the national table. It was no longer possible for any political candidate to ignore the ladies, on either side. The feminists’ resolutions, 25 of which passed successfully, became their National Plan of Action. The Schlafly Eagles, not to be underestimated, were already a media campaign ahead of the ERA proponents. Ultimately, the Equal Rights Amendment, which was three states short of ratification at the time of the 1977 First National Women’s Conference, was not ratified. Diana Mara Henry did not personally know many of the people she captured on film, but she rendered the dignity and honor of each individual, regardless if she/he were anti or pro women’s movement. Her classic Houston images inform, educate and confirm the words of commissioner Elizabeth Athanasakos: “if you had something to go to in your lifetime that was the meeting.”

To contact Dr. Amy Forss, email: aforss@mccneb.edu Thank you!