| DMH Spotlight - Sabra Ferguson's analysis for Texas Women's University: "Houston Makes History" 4/20/2011 | Back |

"One photograph I am interested in is called 'The Last Mile of First National Women's Conference'. It depicts Bella Abzug arm in arm with the runners bringing the torch in to the National Women's Conference in Houston, in November, 1977. What am amazing photo!...I'd also like to use "FNWC Barbara Jordan applauded" in my paper.... Your work is remarkable, and truly captures the spirit of the NWC." -4/20/2011

Sabra Ferguson is a Special Education teacher in Madisonville, Texas. "Houston Makes History" was written for Professor Elizabeth Snapp at Texas Woman’s University for her course Women in Texas History. Sabra has a Bachelor of Science in Psychology from The University of Houston, and is currently completing background coursework for admission into the TWU Speech and Language Pathology Master’s program. She can be contacted at sferguson@twu.edu.

Email us now to add your analysis.

Photographs and text are copyrighted and your request to republish will receive prompt consideration. Thanks!

Houston Makes History

In the 1970s, American women sought governmental protection against rampant violations of rights they felt entitled to. Issues ranging from the right to apply for credit in one’s own name, to the right work outside the home, to the right to choose whether or not to bear a child created enormous debate across the country. When 1975 was declared the International Women’s Year by the United Nations (and subsequently, The Decade for Women), conferences were set up in various international locations (Cottrell). Upon their return from a conference in Mexico City, US Congresswomen Bella Abzug and Patsy Mink authored Public Law 94-167, requesting a national women’s conference in America (Cottrell). Once it became law, PL 94-167 provided $5 million in federal funds to hold conventions at the state level, to be followed by a National Women’s Conference (NWC) to formulate a plan of action aimed at resolving some of the key issues with which women struggled (K. K. Sklar). Federal funds had never before, and have not since, funded such a conference (K. K. Sklar). Throughout the late 1970’s, women all over the country united toward the goal of improving life for women. The participation of Texas women in the NWC provided the leadership and strength throughout the difficult task of uniting 20,000 women toward a single set of goals; for years to come, the camaraderie and networking skills gained in Texas would help those women achieve their goals when the governmental support failed them.

Because the issues that the NWC dealt involved ordinary, everyday women, women throughout the country could relate to the problems they would attempt to solve in Texas (K. K. Sklar). These were not the issues of an extremely wealthy woman with “problems” no one could relate to. These were problems faced by the average American woman, on an average day in America. Problems like being unable to find quality childcare while they were at work, sterilizations being performed at alarming rates, often without the consent of the woman; problems faced by recently divorced homemakers attempting to find a job without experience or workplace skills, providing for children with no assistance from the father or the government due to current laws (K. K. Sklar, The Status of American Women). Women needed help, and they united in an effort to get it.

Upon the completion of conferences at the state level, the National Women’s Conference took place in Houston, Texas in November, 1977. Houston was chosen as the host site for a variety of reasons, but chiefly because key Texas women had been actively pursuing women’s rights, and Houston Mayor Fred Hofheinz had named the first Women’s Advocate for the City of Houston as Nikki Van Hightower (Cottrell). Additionally, several influential figures in women’s rights were from Texas. Within the State Conventions, the representatives for the Texas were quite impressive. Names such as Marta Cotera of Austin, Ernestine V. Glossbrenner of Alice, Eddie Bernice Johnson, of Dallas, Ann Richards of Austin, who would later serve as Governor of Texas, and Sarah Weddington, of Washington D.C., were extremely well known in politically active circles (Cottrell). These women worked together, and successfully secured a place for Texas in the annals of women’s history as host of the NWC.

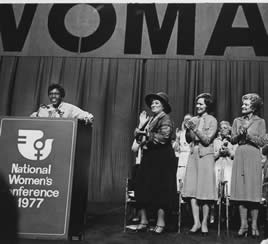

At the National level as well, Texas was well represented. Commissioner Liz Carpenter, journalist and former Press Secretary to Lady Bird Johnson and Gloria Scott, National President of Girl Scouts of America proudly called Texas home (K. K. Sklar, Biographies of National Commissioners). Additionally, Congresswoman Barbara Jordan, Keynote Speaker, and First Lady Ladybird Johnson, who also spoke at the Convention, were from Texas (Johnson). First Ladies Rosalynn Carter and Betty Ford, Gloria Steinem, Coretta Scott King, Jean Stapleton, and Margaret Mead were also in attendance (K. K. Sklar). National attention began to surround the NWC, due to the influential people involved, the amount of Federal funding, and the controversial issues being addressed (K. K. Sklar).

Throughout the state conferences, a polarization had begun to form regarding support f the ERA and several other key issues, such as abortion; once in Texas, the issues intensified with the importance of the National Conference. The ERA had been gathering support and in fact, only lacked the approval of 3 states to become law (K. K. Sklar). Many people viewed ERA supporters, who were often the same key players in attendance at the NWC, as staunch feminists, and painted them as destructors of the American family (K. K. Sklar). The Ku Klux Klan got heavily involved at both the state and national levels, calling press conferences and threatening to march into meetings at the NWC to “protect” their virtuous women who had been “approached” by “militant lesbians” at state meetings. The Mormon Church also denounced many of the platforms women sought, especially abortion (K. K. Sklar). Phyllis Schlafly, of the Mormon Church, stated, “Houston will finish off the women’s movement. It will show them for the racial, antifamily, prolesbian people they are” (K. K. Sklar). The issue of homosexuality also ignited heated controversy. These issues created deep seated division among the women attending the NWC (K. K. Sklar). The leaders of the NWC had their work cut out for them if unity was ever to be attained and useful policy changes were to be proposed.

Liz Carpenter represented Texas well as a National Commissioner, and helped united the women at the Conference through her wit and charm (K. K. Sklar, Biographies of National Commissioners). Speaking in the First Plenary Session on November 19, she began by noting the undeniable similarities that the women attending shared. “We are not all as passionate as Bella [Abzug], as perceptive and photogenic as Gloria [Steinem]…but something of all of them is in all of us….” (Carpenter). She highlighted everyday characteristics they all shared, asking those who had ever held public office to raise their hands, those who were under 30, those who were “somewhere between 40 and death” (Carpenter). She began referencing specific attendees by name, telling their stories for all to hear.

Eighty five year old Clara M. Beyer of Washington, D.C. Retired government worker of 60 years…one of the handful of valiant women who with Eleanor Roosevelt…pushed the reform of child labor…Would you deny [her] the social security rights due her?...Not me! (Carpenter)

Over and over she told the tale of women in the audience, who had sold cookies and cakes to raise money to attend, or who had left several small children at home, or who were currently fighting for the betterment of men, women and children (Carpenter). She asked in each instance “Would you keep from this woman _________?”, and always responded, “Not me!” (Carpenter).

In her capacity as National Commissioner, Carpenter was called upon to speak in several instances. Each time, she united the women and men before her, reiterating the importance of the goals and objectives of the Conference. As she closed the first evening of the NWC, she commented on the 3 remaining states needed to ratify the ERA. As attendees were released to a party the evening before the caucuses began, she stated, “If I should die, don’t send me flowers. Just send me three more States” (Carpenter). Her ability to interject humor into tense situations and her eloquence as a speaker helped to unite the women of the convention to the task at hand. She reminded them that all progress has begun with individuals, but that this event would end with implications for American women as a whole (Carpenter).

![]()

The significance of the event was further highlighted by the use historical artifacts at key moments of the National Women’s Conference. On loan from a museum was the original torch from the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, where the Declaration of Sentiments was written at the first women’s convention in American history. The torch was carried by relay runners from Seneca Falls, New York to Houston, where Bella Abzug ran alongside the runners in a suit and heels for the final segment of the run, approaching the NWC (Bird) (see photo). Additionally, Bella Abzug opened the ceremonies with the original gavel used by Susan B. Anthony at an 1896 suffrage rally (K. K. Sklar). The impact on the delegates was profound. The women knew they were making history in Houston.

The significance of the event was further highlighted by the use historical artifacts at key moments of the National Women’s Conference. On loan from a museum was the original torch from the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, where the Declaration of Sentiments was written at the first women’s convention in American history. The torch was carried by relay runners from Seneca Falls, New York to Houston, where Bella Abzug ran alongside the runners in a suit and heels for the final segment of the run, approaching the NWC (Bird) (see photo). Additionally, Bella Abzug opened the ceremonies with the original gavel used by Susan B. Anthony at an 1896 suffrage rally (K. K. Sklar). The impact on the delegates was profound. The women knew they were making history in Houston.

Another notable event of the NWC was the presence of 3 First Ladies of the United States. Rosalynn Carter, Betty Ford, and Ladybird Johnson met on stage to accept the torch of the Seneca Falls Convention during opening ceremonies (K. K. Sklar). This instance marked the first time the three women had ever fought for the same cause, and the significance of this moment was not lost on the crowd (Bird). Caroline Bird noted, “Their sheer physical presence was more moving than many women expected” (Houston Day by Day ).

Ladybird Johnson was called upon to introduce Congresswoman Barbara Jordan. She began by recalling Jordan’s youth in Houston as an outstanding high school student, then as a member of a stellar debate team at Texas Southern University (Johnson). Ladybird spoke of her as a Texas treasure, that must now be shared with the entire country because of her role as a US Senator (Johnson). Highlighting her climb to the top, Ladybird quoted her husband, “I don’t know where her future’s going to take her, but wherever she goes, we’ll be right behind her” (Johnson). This appealing introduction invited the audience to follow Jordan and support her just as the President had, and initiated an atmosphere of cooperation and unity that would be vital to the success of the conference.

As Barbara Jordan took the stage to deliver the keynote address, to the delight of everyone, she thanked the First Lady for an introduction, “of which I am worthy” (Bird). Her casual demeanor and quiet confidence were evident in her address. She highlighted the responsibilities that each woman held to all other women, in an effort to make the country a better place for women of today and tomorrow. She advised them to accept that responsibility and find solutions, without wasting time pointing fingers of blame at others (Jordan). She acknowledged the differences among the delegates, and urged them not to ignore those differences but to work through their problems in order to arrive at a unified agenda that benefits all women. Pleading that they recall the invocations of both President Lyndon Johnson and Isaiah she asked, “Come now, let us reason together” (Jordan).

As Barbara Jordan took the stage to deliver the keynote address, to the delight of everyone, she thanked the First Lady for an introduction, “of which I am worthy” (Bird). Her casual demeanor and quiet confidence were evident in her address. She highlighted the responsibilities that each woman held to all other women, in an effort to make the country a better place for women of today and tomorrow. She advised them to accept that responsibility and find solutions, without wasting time pointing fingers of blame at others (Jordan). She acknowledged the differences among the delegates, and urged them not to ignore those differences but to work through their problems in order to arrive at a unified agenda that benefits all women. Pleading that they recall the invocations of both President Lyndon Johnson and Isaiah she asked, “Come now, let us reason together” (Jordan).

Though their styles differed, what the speeches of Liz Carpenter, Ladybird Johnson, and Barbara Jordan had in common was a plea for reasonableness and open minds. Their addresses reminded the conference that no group would be able to supply the solutions for the rest of the country as a whole; that no one person is right, nor is one person completely wrong. The cooperation of the attendees was vital, since their numbers were estimated at 22,000 (Cottrell). Representatives hailed from each state, as well as US territories. Each state conference had identified issues that were key in their own states, and the task of uniting all women involved toward a reasonable agenda that served the majority of American women was extremely challenging. The calming demeanors of these influential Texas women would be called upon throughout the conference to work through the challenging issues of abortion, homosexuality, and racial relations.

The organization of the event itself was a crucial ingredient in a successful conference. The procedural rules had been voted on months earlier, and the parliamentary procedures combining Robert’s Rules of Order and Congressional procedures had been established (Bird). Women were to line up at various points within the room with signs of different colors and numbers, indicating whether they were debating the issue at hand, calling for a vote, or questioning parliamentary procedure (Bird). Without fair regulations governing the Conference, and without strong leadership that would enforce those regulations, unity would never have been reached in Houston.

The Conference was led by the National Commissioners, and each was assigned specific planks to preside over during the event. Women’s rights supporters were extremely concerned that the volatility of the issues would create severe dissention among the delegates, and that it would be very difficult to reach a consensus. The make up of the delegation was remarkably representative of the women of the US as a whole, but that also meant that a sharp divergence existed between the extremely liberal and the extremely conservative viewpoints represented (Bird). The historic significance of the event was a constant undertone throughout the proceedings, and Liz Carpenter commented that the event was the “Philadelphia of 1977” (Carpenter), while warning that it would not be a “white-gloved meeting of the colonial dames” (Bird).

The first order of the Conference, unfortunately, was to deal with an objection to the seating of the Mississippi delegation. Mississippi sharply differed from the remainder of the States, because their delegates were all white, though their state was 1/3 African American. The chair ruled the objection out of order, and formally noted that they were unhappy with the election of delegates from that state. The crowd hissed and booed the Mississippian delegates, in support of the African American women who would not be fairly represented (Bird). The sour note of the event could have easily set the tone for a convention that would be filled with argument, disagreement, and distaste, but it did not. The entire body of women spoke the pledge at the conclusion of the Declaration of American Women, “We pledge ourselves with all the strength of our dedication to this struggle to ‘form a more perfect Union’” (Bird). The expert handling of the situation by the Commissioners calmed the situation, and set forth a pattern of fairness and good will that would reign over the proceedings.

The most highly contested issues involved reproductive rights (abortion), rights of minority women, and the endorsement of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). The Minority Women resolution was the first challenging motion to be heard. Caroline Bird describes the air as “electric” when Commissioner Jane Culbreth read the plank to the delegates (Houston Day by Day ). The press quoted anti-change delegates, who predicted the destruction of the conference over this issue (Bird). Minority caucus representatives had worked tirelessly throughout the night to compose a draft of the plank for the NWC. As several caucus representatives read sections of the plank for the delegation, the crowd grew quiet and solemn. It was described as “…something special, almost mystical…” (Bird). Coretta Scott King closed the introduction of the plank urging “the enthusiastic adoption of this … resolution on behalf of all the minority women in this country” (Bird). As the vote took place, delegates quietly watched the results, then broke into cheers of victory as the result of the nearly unanimously vote in favor of the plank became evident (Bird). The Commissioner in charge of this plank was given a standing ovation by the delegates as she left the podium for her outstanding leadership through such an emotionally charged issue (Bird).

The areas of concern addressed by the NWC were: violence against women, political representation, civil rights, economic discrimination, health issues and education (K. K. Sklar). Only one plank was unanimously voted in: advocating women’s equal access to credit (K. K. Sklar). Even the most highly contested debates, those of Reproductive Freedom, the ERA, Minority Women, and Sexual Preference, were approved sixty to seventy percent of the delegates at (K. K. Sklar). Most planks were approved by a margin of eighty percent, a striking note throughout such a controversial conference (K. K. Sklar). The unity that is evident in these statistics speaks to the skill of those who lead in Houston.

Perhaps the best picture of the success of the National Women’s Conference lies in the retrospective report created in 1988 by the NWC Committee (K. K. Sklar). In this report, each plank was revisited, and any progress toward the goals of the original convention was noted. With the failure of the ERA in 1982, many declared the NWC and feminism a failure (K. K. Sklar). The study showed that considerable progress had been made, but not where it had been expected. The progress noted was found at the grassroots level (K. K. Sklar). Women had learned from the NWC. They discovered that it is possible to come to an agreement, to work together and resolve their differences. They learned that they are their own best supporters, fighters, and voices of change. Vast networks of women stretched across the plains of the country, because of contacts made at the NWC. When it became obvious that little Federal support for their rights existed, women began to rely more heavily on these networks established in Houston to accomplish the goals they sought.

The historic significance of the NWC was not lost on its delegates. Those attending stood in awe of the amazing women in their presence, and of their ability to maintain control of the conference in the face of such volatility. Naysayers claimed that unity could not be reached. Nothing could have been further from the truth. Brilliant Texas women such as Liz Carpenter, Barbara Jordan, Gloria Scott, and Ladybird Johnson balanced leadership and authority to guide 20,000 women toward unification. Their successful navigation of the National Women’s Conference through the turbulent waters of change left a legacy of confidence and power for women across America.

Bibliography

Bird, Caroline. "Houston Day by Day ." The Spirit of Houston. Houston, 1977. 119-168.

Cottrell, Debbie Mauldin. "National Women's Conference, 1977." Handbook of Texas Online. 9 March 2011 <http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/pwngq>.

Faces and Voices. By Liz Carpenter. National Women's Conference, Houston. 19 November 1977.

FNWC Barbara Jordan Applauded. Photo. www.dianamarahenry.com. Photographer Diana Mara Henry. Copyright 1977.

Introduction of Congresswoman Barbara Jordan. By Lady Bird Johnson. National Women's Conference, Houston. 19 November 1977.

Keynote Speech, First Plenary Session, National Women's Conference. By Barbara Jordan. Houston. 19 November 1977.

Sklar, Kathryn Kish and Henderson, Sandra. "Biographies of National Commissioners." National Commission on the Observance of International Women's Year, The Spirit of Houston: The first National Women's Conference. Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office, 1978. 243-249.

—. "Summary of Resolutions Adopted by State Meetings." 1977. Women and Social Movements in the United States, 1600-2000. 9 March 2011 <http://ezproxy.twu.edu:2168/was2/was2.object.details.aspx?dorpid=1001257055&fulltext=How did the national women's conference in houston in 1977>.

—. "The Status of American Women." Women and Social Movements. 9 March 2010 <http://ezproxy.twu.edu:2168/was2/was2.object.details.aspx?dorpid=1001257052&fulltext=How did the National Women's Conference in Houston in 1977>.

Sklar, Kathryn Kish and Henderson, Sandra, ed. "Public Law 94-167." National Commission on the Observance of Interantional Women's Year, The Spirit of Houston: The First National Women's Conference. Washington D.C.: US Government Printing Office, 1978. 251-252.

Sklar, Kathryn Kish, Dublin, Thomas, Henderson, Sarah, and Weible, Corinne. "The Spirit of Houston, The First National Women's Conference." Women and Social Movements in the United States, 1600-2000. 9 March 2011 <http://ezproxy.twu.edu:2168/was2/was2.object.details.aspx?dorpid=1001257045&fulltext=How Did the National Women's Conference in Houston in 1977 Shape a Feminist Agenda for the Future?>.

The Last Mile of the First National Women's Conference. Photo. www.dianamarahenry.com. Photographer Diana Mara Henry. Copyright 1977.