In Le sel, la cendre, la flamme [Salt, Ash and Fire] by Henri Rosencher, chapters of historical and political analysis, entitled “Vichy France and its Jews” alternate with chapters detailing his personal adventures. His personal story is “action-packed," describing as they do how young Rosencher, a medical professional and a Jew, takes on the Nazi empire.

Some outstanding episodes are “Instructor in Algiers,” which presents the maturity of his martial expertise in the service of the British; “My Departure for France” and “ My Mission on French Soil” which give a close-up of the intricacies of integrating into a of society at war with its government, and this chapter, “The Tragedy of the Vercors” which is a gripping insider’s narrative of the controversial betrayal by the Allies of the most promising insurrection in Western Europe - from which very few survived to tell the tale. "The Struthof” briefly describes the least-known (in the U.S.) of the major Nazi concentration camps.

Dr. Rosencher resides in Paris with his wife, and on my visit with him in December of 2,000 he summarized his book, in his inscription to me, as “memories of somber but exalting times.” Here is a chapter of Dr. Rosencher’s book, winner of the prestigious French “literary Prize of the Resistance,” in the English language.

Salt, Ash, Flame

by Henri Rosencher .

Paris, 2000: Editions du Félin 10, rue La Vaquerie 75011

"Tragedy of the Vercors"

[unnumbered chapter, pages. 269 -301]

[Translator’s note:

Maquis: A rural locus of the French Resistance.

Maquisard: Resistors fighting from a rural base.

I have kept these in the original language as they are terms particular to the time and place.]

“Here Begins the Land of Liberty”

I wandered about, alone, in the mountains. One afternoon, having climbed among arid peaks, I came to some almost vertical icy slopes, where it was so hard to go forward that I had to crawl. As I was coming up to a crest sparkling with ice, all of a sudden, from the other side of the divide, a face appeared, staring straight into mine, a face that looked just as shocked as I felt. We halted, and stared at each other in silence. Finally I said to him,”Hello,” and he answered me, “Hello.” Then each of us pulled ourselves up, threw our legs over the icy crest, and, after saying “goodbye,” moved off in opposite directions, quickly losing each other from sight. Where was my unforeseen companion headed? What became of him? Is he even alive yet? We passed each other by, in this combat, and we might have been incomparable friends; but, shouldering our missions, each of us moved toward our hidden destiny. I have never forgotten that unbelievable encounter, in a wasteland of ice.

On the morning of the 17th of June, I arrived in the area of Lus-la-Croix-Haute, the maquis under the command of Commander Terrasson. They were waiting for me and took me off by car. The job at hand was mining a tunnel through which the Germans were expected to pass by train. The “Rail” resistance network had provided all the details. My only role was as advisor on explosives. TNT (Trinitrotoluene - a very powerful explosive) and plastic charges were going to collapse the mountain, sealing off the tunnel at both ends and its air shaft. When I got there, all the ground work was done. I only had to specify how much of the explosive was necessary, and where to put it. I checked the bickfords, primers, detonators, and wands. We stationed our three teams and made sure that they could communicate with each other. I settled into the bushes with the tunnel’s entrance team. And we waited. Toward three p.m., we could hear the train coming. At the front came a platform car, with nothing on it, to be sacrificed to any mines that might be on the tracks, then a car with tools for repairs, and then an armored fortress car. Then came the cars over-stuffed with men in verdi-gris uniforms, and another armored car. The train entered the tunnel and after it had fully disappeared into it, we waited another minute before setting off the charge. Boulders collapsed and cascaded in a thunderous burst; a huge mass completely covered the entrance. Right after that, we heard one, then two huge explosions. The train has been taken prisoner. The 500 “feldgraus” inside weren’t about to leave, and the railway was blocked for a long, long time.

“With the Maquisards “

Bucked up, I took off again. This time, André drove me, in the same car that they had given me in Marseille. By that evening, I had arrived at Saint-Martin-en-Vercors.

Two brilliant Parisian surgeons, Fischer and Ullmann ran its very well-appointed country hospital. They practiced under the direction of an older surgeon from Romans, Dr. Ganymede, who was there with his wife and his young son. About forty wounded men were being treated there, including ten Germans. They were astounded by the care they were being given. They thought that “terrorists” like us would have massacred them or left them to croak. It was hard for them to free themselves from the propaganda to which they had been subjected. The Germans, on the other hand, tortured and finished off all of our wounded men they captured alive.

That was where I would spend the next month, each day ten times more meaningful than an ordinary day.I could barely sleep, there was so much to do. I made the acquaintance of Colonel Hervieux, whose real name was Huet, to whose headquarters I had been assigned.

On June 20th, the evening I arrived, Colonel Hervieux briefed me on the development of Resistance in the Vercors and their most recent aremed encounters.

Doctors Eugene Samuel and Pierre Dalloz were the two men who started the Maquis in several parts of the Vercors region.

In 1937, Dr.Samuel, a resident of Pontoise, decided to go live with his family in Villard-de Lans, in order to care for his son there. After the armistice of 1940, he gathered about him a group of patriots who refused to accept defeat.

Pierre Dalloz, editor-in-chief of Club Alpin, the magazine, left Paris to flee from the German occupation and took refuge in Sassenage, in the departement [administrative region] of Isère. In the autumn of 1941, Député [regional elected representative] Raymond Guernez had put Dr. Léon Martin, of Grenoble, in charge of reorganizing the Socialist Party and of distributing Le Populaire, the underground newspaper. In November of 1942, this same Dr. Martin entrusted Dr. Samuel with finding a safe haven deserters from the STO. [Compulsory labor service in Germany for young men from the occupied countries.]

Thus, in December of that year, the farm in Ambel became the first encampent in the Vercors. Thirty Polish Jews, who had just arrived from Warsaw in flight from the Gestapo, and an Alsatian Jewish dentist named Rosenthal, joined the deserters.

But very soon, due to the constant influx of fresh Maquisards, for the most part young men who refused to go to Germany, a succession of camps would spring up: the second camp, in January 1943, near Corençon; three more in February, another three in March, and finally the ninth and last one in April, 1943. These last eight camps were organized and trained in military fashion.

It was Pierre Dalloz who founded and conceived the Plan Montagnard [Mountain Man Plan].

In March 1941, he mentioned the Vercors plateau to his friend Jean Prévost (known as Goderville in the Resistance), a Parisian writer who had retired in Lyon. He described to him this immense plateau, almost entirely surrounded by gigantic cliffs, that could serve as an isolated and protected fortress for parachute bataillons. Slowly, the idea took hold, and Dalloz outlined, sharpened and refined it.

At the end of December, 1942, with Jean Prevost as their intermediary, Dalloz had a conversation with Yves Farge, the regional director, who enthusiastically adopted his plan. Farge first obtained its approval by Jean Moulin, national director of the Resistance, and then by General Delestraint, who was in charge of the secret army of the Resistance. The General went to London and presented the plan to the BCRA [Bureau Central de Renseignement et d’Action, the Free French central intelligence and operations bureau]. Both they and the Allies approved it.

In November, 1943, Pierre Dalloz crossed the border between France and Spain on his own and made his way to Algiers in order to flesh out his plan. In February 1944, he took off at last for London to contact representatives of the fighting French and the BCRA.

Wherever he went, Dalloz insisted on the absolute necessity that certain conditions obtain if his plan were to succeed:

“The enemy must be taken by surprise, and be anxious and disorganized, if the Vercors card is to be played. It’s not a question of taking on an enemy who is in full possession of his faculties, but of aggravating his disarray. It’s not a question of becoming entrenched in the Vercors, but of finding a foothold there from which to go out and attack. It’s not a question of holding fast, but of pushing out in all directions.”

In Dalloz’ thinking, therefore, the Vercors was to be a drop zone for airlifted troops, who were meant to leave the plateau immediately with members of the local armed Resistance, in order to carry the guerilla warfare outward to all the surrounding areas.

The BCRA named the plan that Dalloz presented the Plan Montagnard.

The first first weapons were parachuted in at the end of 1943. The airdrops, few and far between, bought in only skimpy amounts of small arms. The British, who furnished the weapons, controlled their distribution and their use. As a result, conflicts between the various networks broke out, as well as misunderstandings between the Resistance in the homeland and London, which was criticized for not providing adequate arms.

Back in London two months after being sent out by the BCRA, Bingen gave an admisrable description of the problem in his November, 1943, mission report to the Delegation of the Resistance:

“For lack of weapons, the Maquis will dissolve, and no new resistance groups will spring up.”

“It is incomprehensible today, that the day before the liberating invasion of Europe - what am I saying, the day after the first assault wave, in Italy - when all of France, at the cost of bloody sacrifices, has gotten a grip on itself and its finest sons are just waiting for the means and the sign to finally make a joint contribution to the victory, that the means are not being provided, when those means exist, when everything has been set up to get them to their destination and when the immense secret army of French patriots is organized and ready to act.

“In the southern zone, everything is in place for a massive arming of the French resistance, .

“Everything that is happening makes it seem as if de Gaulle, or England, does not want to arm the French Resistance.

“The weapons arrive under total control of the English and, even after they arrive in France, are distributed by British officers on mission there, whose money and promises of more weapons - promises they often keep - pay for sincere or last-minute French good will.

“It is via Buckmaster that most of the weapons the British send get to France.”

His frank and firm conclusion was as follows:

“The best appeasement is to furnish French patriots the weapons allowing them to fight like Frenchmen, in a battle that, at one and the same time, will liberate France and destroy the Hitler nightmare.

“We need weapons.

“We are counting on de Gaulle and on the CFLN [French Committee for National Liberation].

“We are counting on the loyalty of the Allies.”

The problem with the inadequate supply of weapons and their preferential distribution to selected networks was a source of irritation at the heart of the Resistance. The FTP [immigrant freedom fighters organization] was shut out for a long time.

To this day, the paucity and delay of the air drops, despite pressing, unceasing and pathetic appeals, are still a mystery. Any possible explanations are either revolting or incomprehensible.

The large encampments of Maquisards, too little- and too lightly armed, in their midst of the surrounding unarmed civilian population, were another severe problem. These civilians were trapped and could become the victims if the Germans attacked by air or on the ground. The Wehrmacht and the SS could target them with their men, their heavy weapons, their tanks and their air force.

As early as late February, 1944, Didier Cambonnet, one of the heads of the R1 Secret Army, wrote to the BCRA:

“Speaking of the types of redoubts such as exist in the Vercors, two scenarios are possible:

1) Should the enemy decide to throw all its means into play to liquidate the camps, there is no doubt as to the outcome of such an operation. Given the manpower ratio, it would be overwhelmingly unfavorable to us. The plateau would be cleared and its population massacred.

2) Should the enemy dread a confrontation and decide to block the exits, they would turn the plateau into a sort of concentation camp, where the most outstanding constituents of the resistance would be emprisoned.

If we close ourselves in, and choose locations that may be easy to defend, they will also be easy to isolate. Against our wishes, we will have assisted our adversary in neutralizing all the active elements of the Resistance.”

The BCRA should have hearkened to that prophetic message.

On the eve of D-Day, 450 resistance fighters were living in the Vercors, thanks to the support and complicity of the entire population, who provided mostly for their food and clothing.

They were under the command of career officers. Captain Durieux (real name: Costa de Beauregard) commanded the northern sector, and Captain Thivolet (Geyer) commanded the southern sector. Colonel Hervieux (Huet) was military commander-in-chief.

Civilian leaders were Goderville (Jean Prévost) for the North and Doctor Samuel for the South. Clément (Marius Chavant) was civilian commander-in-chief.

On May 17th, 1944, with Dalloz in London, two envoys from Vercors central command arrived in Algeria: Clément and Raymond (Jean Veyrat), the military envoy. With Colonel Constant of the BCRA, they determined where in the Vercors planes and troops could land.

On the June 5th, 1944, in London, Pierre Dalloz was summoned to accompany two officers of the BCRA’s operations service. To his great surprise, he discovered that his report on the Maquis of l’Oisans never reached them, as he had intended it to. The file was finally located in the same building, on a lower floor, in the command headquarters of General Koenig, head of FFI [French Forces of the Interior]. The report moved up one floor and finally got to its destination.

Dalloz repeated that surprise was indispensable, that the Vercors could not be used before the Allies were about to land on the shores of the Mediterranean, and that massive air supplies of manpower and materiel would be necessary.

No heed at all would be paid to any of this!

On June 7th, 1944, Clément returned from Algiers with written orders to put the Plan Montagnard into action.

The Resistance mobilized. The Vercors became a republic. Clément, a debonair giant endowed with ferocious energy, ordered signs posted all over the Vercors: “Here begins the land of Liberty.”

“Enthusiasm”

On June 9th, applying the directives, Colonel Hervieux sent out the orders for the Vercors to mobilize. Three thousand men gathered forthwith on the plateau. But two thousand had no weapons.

As early as June 10th, captain Bob (Bennes), who was in charge of airdrops, begged Algiers:

“Reminding you of urgent need for airdrops of arms and men in the Vercors area. We are able to accommodate at least a regiment of paratroopers. Mobilization accomplished in the Vercors, but current armament completely insufficient. We will not be able to resist if attacked. Lacking light and heavy weaponry for two thousand in the Vercors fortress region. Urgent need to arm

and equip them. We are standing by night and day at landing field at Vassieu and both fields at Saint-Martin.”

On that same 10th day of June, Lieutenant-Colonel Descour, assistant to R1’s regional chief, cabled Algiers: “Vercors. Two thousand volunteers to be armed. Initial enthusiasm sagging because weapons lack. Extremely urgent send men, weapons, gasoline, tobacco in next 48 hours max. Enemy attack possible. Current conditions render effective resistance impossible. Failure would mean pitiless reprisals. Would be disaster for region’s Resistance.”

On June 11th, Descour again insisted: “Not keeping promise now will create drastic Vercors situation.”

On June 12th, Bob forged on: “Urgent send maximum machine guns and mortars and if possible canons and antitank weapons.”

On that same day - June 12, 1944 - in response to these urgent and beseeching appeals, London sent the Vercors the following stupefying counter-order:

“Send the men home, premature mobilization.”

Colonel Hervieux had executed a written order for mobilization. The counter-order sent him into an indescribable fury. He responded: “Damned if we’re going to run off after having compromised the whole population and without any opposition.”

Enthused by the mobilization and the resumption of the struggle, and to galvanize the population, the Maquisards draped a huge French flag on a promontory overlooking Grenoble. It served to mock the German troops stationed near Saint-Nizier, but would cost very dear.

Crazed by rage, the Germans assembled 400 men at Tour-sans-Venin, and on the 13th of June mounted an assault on Saint-Nizier. The battle was engaged with an equal number of Maquisards. The Germans were stopped and forced to leave the field after 12 hours of combat.

On June 15th, at dawn, the Waffen SS attacked again, this time in force, led by artillery - 105 mm canons - with air support from the base at Chabeuil and assistance from the miliciens (French fascists.) The miliciens wore the same red, white and blue armbands as the Maquisards, sowing confusion among the Resistance. This time, the Nazis reached Saint-Nizier, which they burned and destroyed almost entirely.

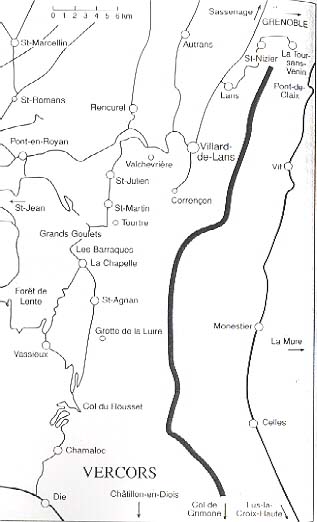

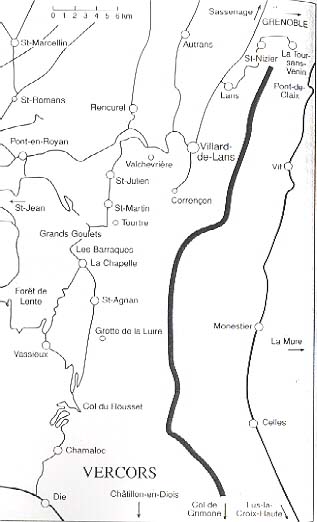

The Vercors, I thus learned, bore a gaping wound on its Northeast flank, open to German penetration by way of Lans and Villard-de-Lans.

Since general mobilization had been proclaimed on June 9th, veteran policemen rallied to the Resistance. They knew everyone. They carrried out the mobilization orders. Very soon, three thousand young people had gathered, but we had weapons only for a thousand men.

That’s how things stood when I arrived in the Vercors. I sensed how anxious Colonel Hervieux was about the lack of small arms and of heavy weapons. But he was full of hope that Algiers would intervene as foreseen in the Plan Montagnard and as Algiers had formally pledged to the civilian and military leadership of the Vercors.

It was most urgent that weapons be procured. Hervieux charged me with requisitioning all of the area’s existing weapons. With the help of the police, we gathered a hundred or so rifles used for mountain-goat hunting and a few old Mausers. That didn’t go too far.

The 24th of June was St. John’s Eve. The young people lit fires in the pastures that night. Capering and singing, they jumped through the flames. I remember one of the songs for that holiday. Its refrain was “ You, whom I loved so...” I learned it and sang along, eyes fixed on a young dark-haired beauty. When I spoke to her, she told me she was the liaison between the Vercors and Grenoble, and that her name was Jeannette. I sighed and kept my admiration platonic. Between us, in the Resistance, friendships were warm and fraternal, which made our relationships easy, direct, unmanipulative, spontaneous, generous and disinterested. We were all devoted to the same cause, for which we were prepared to give our lives.

Our enthusiasm matched the beauty of the landscape. The Vercors is grandiose, with its awe-inspiring peaks and cliffs, its joyful gently rolling plains, its trout-filled trilling brooks, its sunny plateaus dotted with innumerable sheep, its somber, steep and terrifying gorges churned by hurtling torrents, foaming as they go. Its fractured boulders require ankles equal to any challenge, and its impenetrable forests were a hideout for the Maquisards.

Every single day, for more than a month, messages went out to Algiers, reminding those who had given the order for the uprising of their responsibilities, urgently - insistently - requesting shipments of heavy weapons: antitank canons, mountain canons, heavy artillery and mortars. Each message stressed the imminence of a powerful German attack, the inevitable defeat of the Resistance if it remained lightly and insufficiently armed, and the reprisals that the region would suffer, including the massacre of the civilian population.

Joseph and Hervieux also gave me lists of heavy war matériel to ask for from Algiers. I coded the messages and addressed them to the BCRA, with no more success than Bob had had with his contacts. All we got were light weapons: automatic pistols, Sten guns, grenades, rifles, submachine guns and light machine guns.

I became once again the arms instructor that I had been at the Club des Pins in Algiers. The young volunteers learned quickly.

In the evenings, I found myself at dinner with my two superiors, exhanging news and friendly conversation. Colonel Hervieux and I soon became firm friends. I profoundly admired the skilled command of this superior career officer, his intelligence, his ability to adapt to guerilla warfare, discarding the hierarchical military structure in which he had been trained. I found out from him that he came from a long line of officers. He graduated from St. Cyr [the French equivalent of West Point] and fought for several years in Morocco, for which we shared our enthusiasm. I also reconnected with General Joseph, whom I had already known at Barcelonnette. He also greeted me with friendship. Both granted me the men and available materiel that I asked for. But first I had a friendly run-in with General Joseph, who maintained that the Vercors, surrounded as it was on all sides by straight cliffs, was a fortress that could never be taken. I called his attention to the routes by which it could be penetrated, the wooded slopes that led gently from the valleys up to the high plateaus. He came around to my way of thinking, as did Colonel Hervieux. A decision was taken to mine the roads in, and to place traps in the forests. Then and there, I organized sabotage training for the mountain forces, with each of my trainees becoming trainers in their separate corps. In short order, a hundred of the young mountain men carpeted the forests of Corençon and Lente with traps.

The best mine locations were chosen by Garnier, a wildlife officer of about fifty, indefatigable man of the mountains who knew the Vercors from end to end and often served me as a guide when I crossed the magnificent and tormented regions on foot.

One of the armed mountain men, Captain Francoeur, former surveyor, was put in charge of mapping out all the mines. But during the course of the ensuing battles, he was killed, and the map was lost. (Years later, passing along its edge, I noticed that the Lente Forest was fenced with barbed wire and signage warning "Danger-Mines in Forest.")

Nor did I forget my health-care mission. My hospital colleagues provided me with long lists of medical and surgical necessities, that I spent the nights putting into code to send to Algiers. And that material arrived in containers airdropped onto the parachute landing fields of Vassieux.

A dozen doctors, rather elderly but wholehearted in their desire to serve, arrived to form the health-care task force. I spread them out throughout the countryside, which did not thrill them.

Other doctors were less willing. I learned that a Parisian MD was in Villard-de-Lans, and that he refused to come. I had two policemen go fetch him, and he arrived at Saint Martin one morning. He protested he was too old, incapable of staying out in the maquis, and ignorant of anything but his specialty, the treatment of TB. I reminded him that I had trained under him; then I reassured and flattered him by catapulting him to Commander in Chief of Health Services in the Vercors. He used this later to make the case for receiving official rewards.

I organized a school for stretcher carriers and nurses and put him in charge.

In the midst of all this, I also took part in the sabotage of a German listening post, set up near Valence, a giant earphone turned toward the planes coming from the Mediterranean. We went out on the expedition by motorcycle, and racing back from it, I was the passenger on a motorcycle that hit a mine. I was thrown, knocked out, and got back up with a fractured shoulder. My driver, Captain Francoeur, got off with a few bruises. The trip back was agony. Fisher suited me up with white bandages that pulled my shoulders back, and my buddies jokingly called me "Little Wings." I didn't have time to stop and continued my work in this outfit.

I am speaking only of my activities, which were all I knew of; there was no time for me to get a view of the whole operation, which was reserved for our commanders-in-chief. But I know that what I did was only a minute part of the whole of the Resistance in the Vercors. I could see that from the exalted and tragic air of Joseph and Hervieux, who shouldered responsibility for the whole operation.

In the evenings, when I dined with Colonel Hervieux, he would bring me up to date. All around the edge of the Vercors, the battle was raging. As early as the 17th of June, before my arrival, our Maquisards had overcome the Germans at the pass of Ecourges, near Saint-Nizier.

On the day after my arrival, the 21st, our Resistors stopped them at Rencurel.

On the 24th of June, the Resistance liberated 53 Senegalese marksmen from Lyon, along with their junior officers, all of whom had been imprisoned by the Germans, and who came to join our ranks where they came under the command of lieutenant Moyne.

On the 26th of June, the Resistance stopped all rail travel through Grenoble toward Lyon, toward Valence, toward Chambéry, and cut all telephone and telegraph communications in the region.

On the 28th of June, our Maquisards stopped a connvoy of ten trucks and a hundred Germans at Rochette-sur-Crest.

These exploits lifted our spirits.

But, from Josph's and Hervieux' feverish and exhausted look, I sensed that the situation in general was constantly worsening. The German forces almost always were taking and keeping the offense. Their assaults, that came mainly from the North and the South, little by little encircled the redoubt. In succession, they took:

on June 19: Villard-de-Lans;

on June 22: the Combovin plateau;

between July 4th and the 6th: the Grimone pass;

on July 10: Lus-la-Croix-Haute.

And that continued up to July 20th. Day after day, we lost men and ground.

The German forces had an airfield at their disposal at Chabeuil. Twenty kilometers from the Vercors, the round trip took ten minutes. Their fleet of sixty planes dominated the skies of the region with constant overflights to observe but more often to machine-gun and bomb.

On June 15th, that Nazi air force supported the German attack on Saint-Nizier.

On June 28th, it intervened to save a German column attacked by the Resistance at Crest. It bombarded and partially destroyed Saint-Nazaire-en-Royans, then Pont-en-Royans. On June 30th it did the same to Crest, in reprisal.

Each bombardment destroyed and burned tens of homes and killed tens of civilians. The wounded filled the hospital of Saint-Martin-en-Vercors to overflowing.

On June 22nd, the Resistance of the Vercors asked the Allied Air Force to destroy the airfield of Chabeuil and the fleet of planes stationed there.

For a month, daily messages pleaded for that bombardment. The BRCA transmitted the request to the Allied High Command at Naples. But the Allies refused to modify their plans and put it off indefinitely.

Fortunately, July 14th lifted our morale with an exalting spectacle. The Allies gave us a surprise worthy of our cause.

At 9:30, the sky buzzed, and soon a flottilla of planes too numerous to count appeared. The sky was filled with a hundred Allied planes that sparkled in the sun, manoeuvering by the dozen. There were 62 flying fortresses, protected by scouts. They sowed hundreds of parachutes that blossomed in the blue sky like white flowers, descending joyfully, bring about twelve hundred containers. It was a magnificent celebration. The planes beat their wings to salute us, the ski was full of them. It was more beautiful than any fireworks display. It was a grandiose, fairy tale, exalting spectacle. The Maquisards' enthusiasm was indescribable.

The celebration lasted a half-hour. But it was followed by an infernal round of attacks by German scouts and bombers from Chabeuil, the airfield ten minutes away. It was a uninterrupted harrying, that lasted from 10 to 5, meant to prevent the Maquisards from taking possession of the containers.

At 3, Vassieux was devastated by incendiary bombs, and at 6, so was la Chapelle-en-Vercors.

We had to wait until nightfall to collect the airdropped containers. As always, these contained only light weapons, and a few submachine guns.

In the evening of July 14th, despite this drama, we spent a magnificent night around a camp fire. We sang gay refrains, nostalgic tunes, old songs; the atmosphere was intoxicating. That was where I rediscovered Jeannette. my pretty mountain lass who was most willing to connect. I was in love with her, and I didn't even have time to court her. Smiling, simple and charming, she sweetly let me admire her. Other couples connect, timidly, most of them platonically. Hearts quickly caught fire in those exalted days when lives are in such danger that tomorrow didn't exist.

The hospital of Saint-Martin-en-Vercors was full. The wounded had been flooding in since the end of June, following the bombardments of Saint-Nazaire-en-Royans and Pont-en-Royans. Every day the wounded, victims of exploding shells, arrived: women, children, even a nursing babe seven months old. From the 12th of July on came the victims of the bombardments of La Chapelle, then of Vassieux, finally those of the landing field.

On July 15th, the hospital being overfull, the wounded were transported to Tourtes, three kilometers away. On that same day, we expected a massive attack by German troops; each day we received warnings of increasing formations of Nazi troops.

On July 16th, our Maquisards captured eleven collaborators at Villard-de-Lans.

It was one of the last items of good news in those dramatic days.

In the evening of July 20th, at dinner, Colonel Hervieux painted the situation for us:

The Vercors was completely encircled by the enemy.

What was the strength of their forces? On the German side, it was said there were four thousand men coming from Saillans, as many from Chatillon-en-Dioix, and three thousand from Saint-Nizier.

All in all, the Resistance in the Vercors estimated that it was surrounded by thirty thousand men. In Grenoble alone, for instance, the daily ration was 15,000 loaves of bread.

Algiers thought there were only ten thousand in all.

There were certainly five divisions, two battalions of which were mountain forces, with a group of mountain artillery men and an armored regiment.

The German forces were equipped with heavy artillery, numerous 45mm canons, 18 105 mm canons, mules for mountain combat, and automatic machine guns. Since July 18, six heavy tanks and 20 light-weight tanks had arrived near Chabeuil.

Those land forces were supported by the air force, which, from July 12 on, took off from the airfield at Chabeuil just ten inutes away to incessantly bombard and machine-gun the entire Vercors, and La Chapelle and Vassieux in particular.

(The bombardment of Chabeuil, requested since June 22, finally took place on July 27.)

On our side, the defense was comprised of less than two thousand men aremd with pistols, Sten guns, rifles, grenades, and some Thomson submachine guns.

On that 20th of July, the Vassieux airfield was ready. Because of the incessant German airstrikes. It had been impossible to work there during the day. Thanks to crazed nightly efforts, during ten nights of work by the Maquisards and the general population, the installation of a high-voltage wire and the preparation of the plateau was completed.

The promised manpower to be airlifted in by the Allies was limited to the following support:

On June 29, the first part of the Eucalyptus mission composed of four officers: a Frenchman, an American, and two Britons;

A second airlift the same day of 14 Americans under the command of a captain and a lieutenant, to instruct the maquisards on the use of American rifles and bazookas;

On July 7, the Paquebot mission, comprising four men and a woman;

on July 10, the second half of the Eucalyptus mission, composed of two French captains and a British lieutenant.

These were the paltry armed forces airlifted in by the Allies: 25 men and a woman, after they had promised the massive assistance of numerous troops forseen in the Montagnard Plan.

(The SS, by contrast, on the day after July 21, sent an air transport of five hundred men to Strasbourg.)

To give a good idea of the Allied capabilities, the Mediterranean Air Force, headquartered in Naples, controlled 1900 aircraft.

On July 20th, Hervieux notified Algiers that the attack was imminent, the German forces considerable. As always, he once again asked the Allies to parachute in large number of troops and heavy arms. Algiers promised to send, in the night of the 22nd to 23rd of July, thirty men, 14 officers and junior officers.

Colonel Hervieux concluded: "That's far too few and too late, for the struggle is too unequal."

Abandonment and Massacre

The next day, at nine o'clock, the maquisards and villagers of Vassieux are surprised by the sounds of airplane engines rapidly approaching, and they see, very high in the sky, apppear twenty or so planes towing gliders.

"Here they are, at last!"

"What joy! We've been asking for so long!"

The airfield on which they have been working exhaustingly is about to be baptized.

But a fatal surprise follows immediately. Folkwulf scouts machine gun the field. Heinskels let loose 250 kilo bombs.

From the twenty gliders that landed, bound SS soldiers who spray the field with grenades and machine gun fire. There are five hundred of them that came from Strasbourg, and that were specially trained for this very operation.

Just about all our troops in Vassieux are massacred, along with most of the civilian population: women and old folks 55 to 75 years of age. Children are burnt alive, with old women and old peasants. Men are hung by the neck, feet lightly touching the ground. They die by slow strangulation.

At the same time as this eruption from within , thousands of SS surrounding the Vercors launch the assault.

The news becomes alarming. Outside the forest that the Germans don't dare invade - since our traps are working well - they are moving ahead onto all the roads to the north, the west and the south. The mines go off, but the roads are immediately rebuilt by the enemy's engineer corps, and the Vercors is compromised from the center and from all sides. The battle rages furiously, all day long. Our ambushes stop them for a moment, but their forces are innumerable, they surround us on the heights, and we are constantly forced to fall back in order to avoid being surrounded. The battle goes on for three days.

The hospital is overwhelmed by the wounded. I stay there to help Fischer and Ullmann who operate non-stop, night and day, with Beumier, a medical student like myself. (Beumier is Doctor Blum-Gayet, located in Grenoble. He added to his name that of his wife, Germaine, a Resistance heroine particularly well-known and admired throughout the Vercors.)

Thus begins the martyrdom of the Vercors.

The civil population serves as target practice for the thugs. Women, old and young, and little girls too are raped, old men and children shot down, men hung by the feet die after long agony, others are locked in and burned alive in their houses. The SS shoot anything that moves, massacre man and beast, loot anything that can be taken by the cartload, blow up and set fire to entire vallages. Any Maquisard who is caught is tortured before being killed. Men working in the fileds, shepherds, old folks are mowed down, and the animals too. The SS blow up and burn any isolated farm and house.

The third day, at night, General Zeller, his lips tight with powerless rage, gives the order to evacuate all the Vercors and to fall back wherever possible. All night, we prepare to evacuate the hospital. We are given a trailer, two trucks and a light car that we fill up at dawn. We go south. Our information is that the road going through the Rousset pass is still open. We get there toward eight in the morning, and ride quickly down toward Chamaloc, then get to Die. There, we are stopped by the population: local cyclists have come back in haste, the motorized German troops are one kilometer away and closing in fast. The trailer and two trucks turn around, have to go back into the Vercors. On the way, we pass the front wheel drive Citroën of General Joseph. I want to stop him from throwing himself to the wolves. I suggest we hide the wounded in a huge cave, 350 meters deep, the Grotto of Luire, whose existence I learned of from Garnier, the Fish and Wildlife officer. The General gives his approval. We go back over the Rousset pass, find the little hidden road and set up all our wounded, on stretchers, inside the grotto.

While Fischer and Ullmann take care of their surgical patients, Garnier, Francoeur, Beumier and I get ready to leave. We have one last talk, feeling that we will never see one another again.

Garnier: Hervieux ordered us to disperse, but it's too late. The population will be massacred. Any resistor who is found will be executed. As soon as we were defeated on the 15th of June, we should have left the redoubt and spread our guerillas out, in small unseizable groups. Today, all together, we are caught in a net and completely encircled.

Me: You are right. But Algiers insisted it was an imperative that the Maquis of the Vercors create and hold airfields for Allied airlifts. So we had to stay in place.

Garnier: Yes, but when we realized that we would get neither troops, nor heavy weapons, there was another chance for us to disperse and avoid being surrounded.

Me: I talked about this with Hervieux. But he didn't want to abandon the population that was compromised, and deliver her up to SS reprisals. Moreover, he believed, to the end, that he would receive what the Allies had promised to send.

Francoeur: You saw what the airfield at Vassieux got to be used for! Why didn't Algiers keep its promises?

Me: I'm aghast, just like you are. The Allied forces, with American support, has unmeasurable power. It is not to be believed, not possible, nor admissable, that they could not temporarily pull away from their immense force a few hundred heavy machine guns, a few hundred mortars, a few dozen mountain canon and anti-tank artillery. And since we begged every day. I myself coded some of the messages clamoring for these heavy weapons. And I find it unbelievable that they couldn't send, from their formidable air fleet, the fifty planes that could have dropped these for us.

[to be continued]